HiddenArt – A Russian-linked SS7 Threat Actor

Today, we issued our newest White paper: Spectrum of Violence: Mobile Network -enabled Attacks in Hybrid Warfare . This paper is the first to cover how attacks over the mobile core network could be used as part of any hybrid warfare scenario. In this blog I am including some additional information on the research in the white paper.

The name HiddenArt

HiddenArt is the name we have assigned to a Signalling threat actor (platform) that we believe with a high degree of confidence to originate from Russian network sources. We, like many other companies in the cyber security area, assign names to entities of interest after we have tracked and understood their behaviour for some period of time. The name in this case is comprised of two parts: Unique Feature + Label.

As explained in the report, the 1st part – ‘Hidden’ is used because this is the unique feature we have seen this platform use over the last 5+ years. All attackers using mobile signalling networks try to hide, but HiddenArt is unique in that it tries to make its source SS7 addresses (SCCP Global Titles or GTs) be as similar as possible to real, non-malicious GTs used by legitimate mobile network nodes. Further information on the mechanisms of this hiding is later in this blog. The effectiveness of this is questionable for network that has more advanced protection, but it may give an advantage for a mobile network with less advanced firewalls, as they may not be able to differentiate the traffic from similar malicious and non-malicious sources, and so be unable to block attacks. It also makes attribution much harder as we will see.

The 2nd part – ‘Art’ – was selected not as a compliment, but as a likely origin/user. Art is the Old Irish/Gaelic word for Bear. It stems from the same Indo-European root as the Greek word that gives us Arctic ( arktos == bear / arktikos == under the bear), referring to the land under the bear, meaning Ursa Major or Ursa Minor. We used the term bear as we suspected from an early stage that this threat platform had Russian connections. How and why we did this, bears looking at.

Attributing Russian Direction/control and origin

As covered in our report, there were several pieces of evidence for us to assign an origin and user, below are three sources of information that we used:

Targets

A 1st piece was intelligence regarding the devices which were attempting to be tracked and /or their communications intercepted. We observed concentrated targeting on specific devices, some of which we later learnt were linked to Russian political dissidents. We also observed tracking of individuals who we learnt were VIP individuals – that is individuals of importance in the economic/political sphere. This gave us a clue on the end-user, and the fact that this was not therefore likely to be one of the (rare) Organised Crime Groups using mobile signalling networks, but rather a Surveillance company or a state-level actor. However, this alone would not be enough for source attribution, nor could it tell us what type of entity HiddenArt is.

Behaviour

A 2nd piece was the attack behaviour. First of all, we had to be certain the detected activity was actually malicious. This is harder that casual observers may expect. The vast majority of unusual or suspicious activity in mobile networks is not actually malicious. Believing that it is, gives rise to situations where you must also believe that Canada and Mexico are the biggest executor of mobile attacks on the United States in 2020[1], something that strains credulity. Once you have eliminated the noise, and determined the malicious activity through analysis, we can then categorise it. In this case we were able to establish with a high degree of certainty that the activities were deliberate, that is, human operated attacks for location tracking and interception of personal communications. This objective is squarely in the arena of surveillance companies and state-level actors. However, surveillance companies and state-level actors differ in their behaviour. Surveillance companies like Rayzone and Circles (who are associated with NSO Group) tend to have multiple customers and are often continuously active. This is because they have to be, as they have paying customers and need to meet their needs and requests. The surveillance volumes here are consistent and in specific geographies very large.

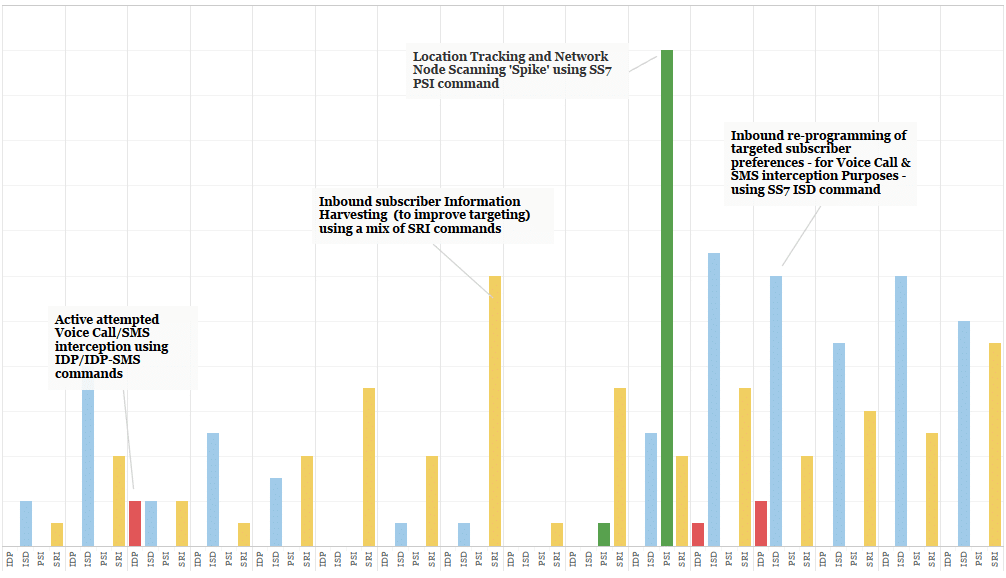

State-level actors tend to be more focused on specific individuals, as part of intensive operations to support wider intelligence activity. Afterwards, some of the specific attack nodes used in any instance by state-level actors may then go dormant for weeks, months or even longer depending on their operational needs and objectives, the relative availability of alternate vectors, and their evaluation of the targeting (security) environment. In our experience both surveillance companies and state-level actors try to do a level of misdirection by targeting innocent subscribers, but sooner or later they both have to revert to their primary target(s) as well as trying to minimise their presence on the signalling network. When we first detected HiddenArt it was engaged in attempted intensive targeting of a few specific individuals, before branching out to track additional targets. Our report includes a diagram of malicious activity over several days which we have re-shown here:

Example Activity of HiddenArt Threat Actor over multi-day period

Since 2018 HiddenArt has been in a semi-dormant state, but it performs periodic network reconnaissance and/or routing verification against mobile networks globally. This is the sign of a state-level actor which is ensuring that its reach and capability is sustained over time.

True Source Analysis – Following the Bear

The 3rd , and most complex piece, is the origin of these attacks. This must be taken with caution, as using signalling source information for attribution requires extensive experience, analysis as well as some stubbornness and luck. All packets routed in mobile signalling networks (3G, 4G, and 5G) have their origination point indicated as a source address. The country of the source address though, cannot be blindly assumed to be the same entity benefiting from the attacks. It has been shown that entities who have been given access to mobile signalling access by Mobile Operators are selling this on to hostile actors. This is the reason why places like the Channel Islands have appeared in the past to be among the biggest sources of malicious attacks in the world. But this is not the same as attribution, – no one would claim that the Government of Jersey or Guernsey have a massive desire to track and intercept communications of people around the world. So even though attacks may come from a network in a source country, that source country may not be the one benefiting.

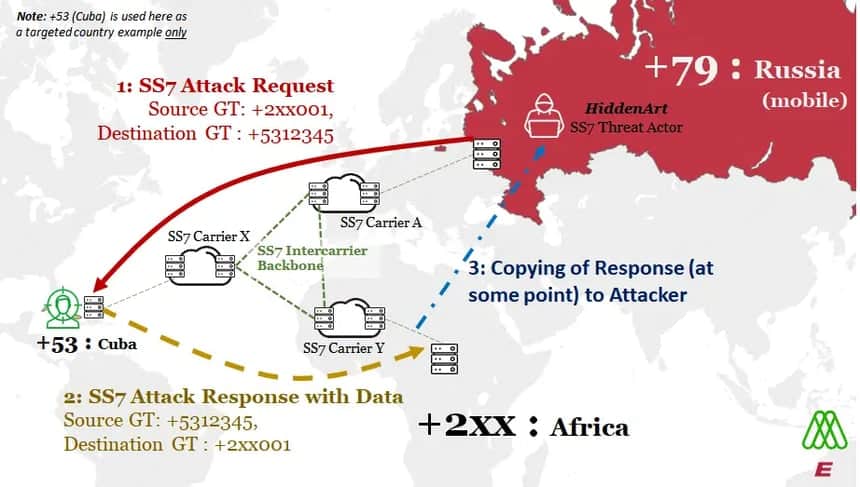

This is complicated, by the little known fact that in 3G (SS7), and especially in 4G (Diameter) where these signalling packets say they come from and where they actually physically come from could be two different things. For HiddenArt, we detected that its purported initial origin point were a group of Mobile Operators in Africa (Note: it has since branched out to use sources from other countries). However, it seemed very unlikely that these countries themselves would be strongly interested in Russian targets. This raised the possibility that either The HiddenArt attackers had access to signalling infrastructure in these countries, or – more interestingly – the attacks may be not truly originating from, these countries.

To answer this question, we had a discussion with the African Mobile Operator group being purportedly used as the source. They were unaware of this activity, and could find no trace of any attacks being sent, but very strangely, could see the responses to the attacks being received in their network. We focused on understanding the attacks first. While there were some suspicions that equipment compromise might have occurred at the start, it seemed unlikely that their equipment was being compromised on a long-term basis. This meant it seemed the attacks were not coming from Africa, but elsewhere. This is possible in theory in SS7 and Diameter networks because the connection between two mobile operators in countries is not normally direct – multiple 3rd party routing companies called inter-operator carriers exist, and each one of those can carry, route and if they wish, redirect a SS7 or Diameter command. We see this redirection in real-life where there have been observed cases where a GT has been leased (rented) or reassigned from one country to another, with the consent of the Lessor. However, this did not seem to be happening in this case. So we had two outstanding questions:

- Where were these attacks really coming from? And

- If the responses were going to African networks, were the attackers getting the responses, and how? (assuming the attackers were not African Mobile Operators)

Validating the Source

A breakthrough for the first question came in the deployment of additional set of firewall logic and filtering rules in a customer site. The world’s mobile operators build their 2G/3G (SS7) security defence on a GSMA document called FS.11 – this is a set of guidelines and principals for detecting and blocking suspicious or unwanted signalling activity. As the editor and a principal author of this document, I am very much conscious that anyone within the mobile operator community has access to this, and it will inevitability fall into hostile hands[2]. While the FS.11 document contains a broad and extensive set of principles and guidelines, it is ultimately up to mobile operators to implement them, and they may naturally focus on the main defensive use-cases. This can give attackers the idea to develop attacks that they think may avoid defences or checks that Mobile Operators will put in place, especially if mobile operators just follow the letter of FS.11 SS7 Firewall rule recommendations, as opposed to going further and putting in detection logic to cover all of its the principals and guidelines.

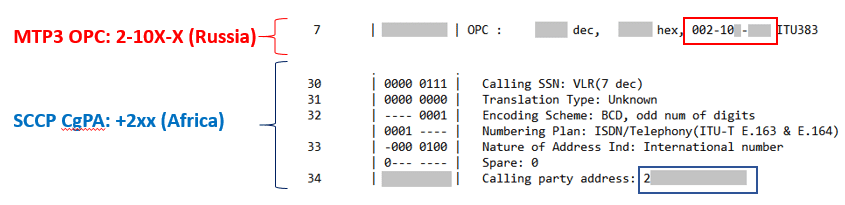

The addition of these new rules allowed us to detect additional abnormal SS7 commands, related to the ongoing attacks, but this time some of them originated from Russian GTs. With this information, with our customer and with the help of multiple inter-carriers we then traced the routing of the main ‘African -originated’ attacks across the SS7 international interconnect links. This is quite difficult due to the need for multiple parties to be involved and the very short time period required to do it in. However, after a few attempts we found that these led back to Russian MTP3 origination point codes (OPCs). MTP3 is the SS7 layer beneath the SCCP layer, and is only valid point to point. This showed that these packets did originate from Russian links, despite what the African source GT address said.

Intercarrier Trace of Spoofed African Global Titles, from Russian Originating Point Code

Continuing an Answer

Answering the 2nd question was harder. To recap this question – was the +7/Russian attacker – HiddenArt, getting back the response with all the info they wanted, if they said in the request that they were +2/African? Because this means the response would be sent to Africa networks only, not Russian network nodes.

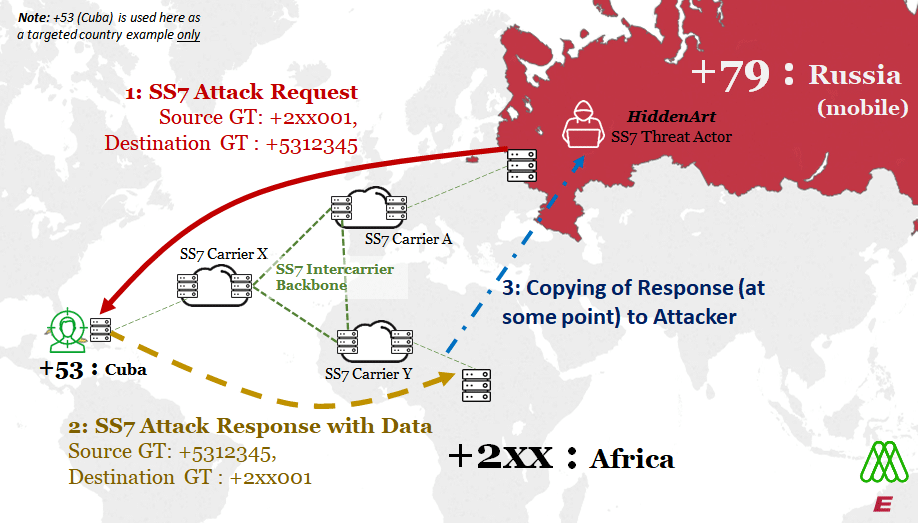

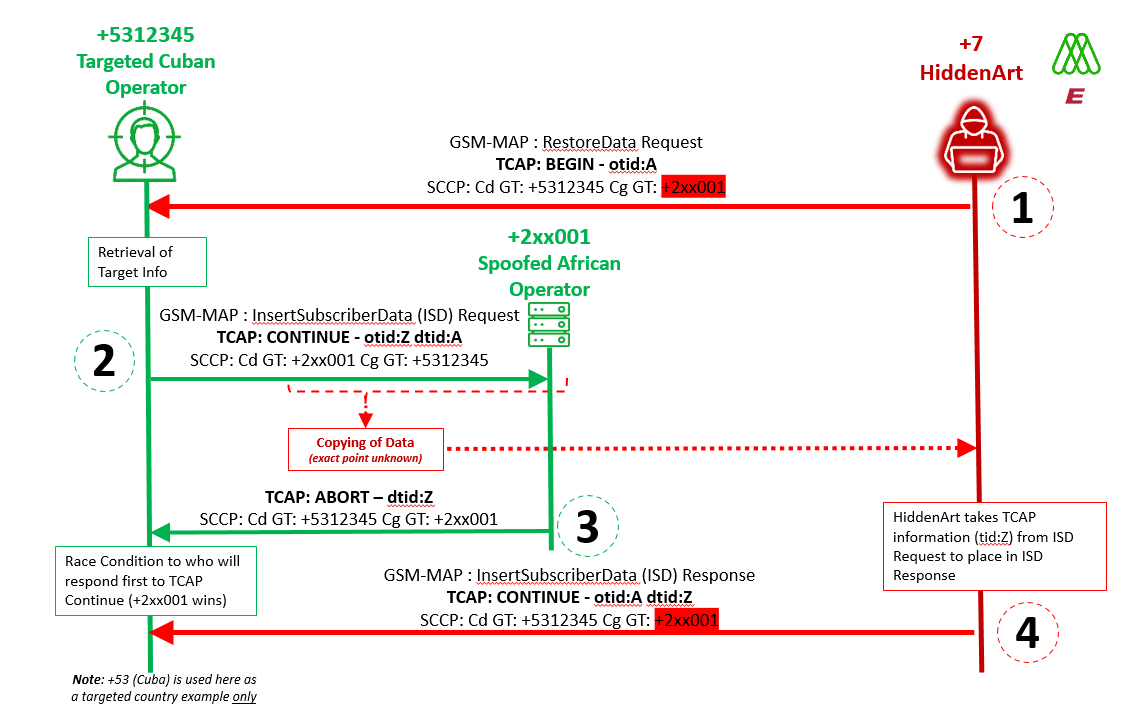

Theorized flow of SS7 Attack on Example Targeted Cuban Mobile Operator

Strong evidence for a solution came from careful analysis, and the fact that sometimes the HiddenArt attacker needed to have a conversation with the victim network. We mentioned already that the mobile operators in Africa told us they definitely received the answers or Responses, even though they did not generate the questions or Requests. This meant that the only logical way the Attackers could have gotten the answer information if it had been copied – not redirected -along the chain somewhere.

But the issue was how to show this. After much research we came across a specific attack sequence involving an African GT that gave us strong evidence for this. The below is the sequence diagram for a SS7 RestoreData attack. In this, the HiddenArt attacker is asking the victim network to give information on a subscriber (information harvesting) . This information is sent in a sequence of InsertSubscriberData request commands, and each request must be acknowledged with a response in order for the sequence to continue. The layer in which the control of this sequence is happening is called the TCAP layer – where BEGIN starts a sequence – or TCAP Transaction, a CONTINUE continues it, and a END stops it.

Sequence diagram of RestoreData/InsertSubscriberData Attack, showing two responses to one request

What we observed was:

- HiddenArt (spoofing the African +2 network) sent a RestoreData in a TCAP BEGIN to the victim’s network – we have selected Cuba as an example in this case. RestoreData is used to trigger a response with the targeted subscribers detail, in effect , subscriber information harvesting.

- to which the Cuban network responded with an InsertSubscriberData Request with the subscriber’s victims details, in a TCAP CONTINUE, to be sent back to the +2/African network, containing the unique transaction ID (TID) Z.The next point is very interesting, the victim’s network receives two responses to this continue:

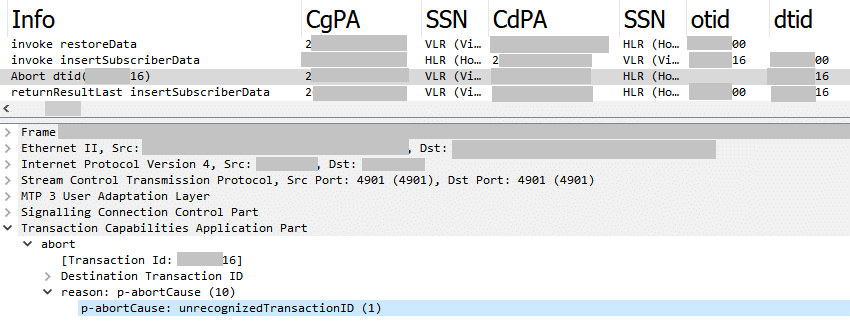

- The initial response is a TCAP Abort. In this we believe the real +2 network is saying it does not understand this sequence involving a ISD it just received (this is an Abort code of Unrecognized TransactionID )

- The 2nd response is a TCAP CONTINUE. In this we believe HiddenArt, spoofing the +2 network, is saying it does understand the sequence involving a ISD it received, and is sending back an InsertSubscriberData Response , to keep the conversation going. This ISD response contains the unique transaction ID (TID:Z) sent in step 2

This step 4 proves that the information sent by the Cuban network in step 2 is not lost from the attacker perspective, and is received by HiddenArt, otherwise they would not know and when to respond to the ISD in step 2 with the right transaction info.

We picked this attack sequence to discuss because intriguingly, it also shows strong evidence that the data was copied somewhere along the path. If you look in step 3 above, the spoofed network says it does not understand what it just received. What we believe is happening here is a potential race condition in steps 3 and 4, between the spoofed African operator and the HiddenArt attacker. We believe both the attacker network and the spoofed +2 African network get the ISD sent in step 2, and they are in a race to respond. Normally the African networks’ GTs selected to be spoofed by HiddenArt completely ignore the responses they receive, but in this case the response was part of a transaction sequence, and the GT selected was similar enough to be answered with essentially a “I don’t understand this conversation” response from a real network element in the +2 African operator. In SS7, the same network element would not answer a sequence in two different ways, so the logical explanation is two different network nodes got the ISD response information: one over the SS7 path (the spoofed +2xx001 node), and one over some other copied means, and then both attempted to answer. We observed this response consistently when this particular GT was used, and not for other RestoreData attacks, using different spoofed source GTs. A wireshark capture of this attack is below.

Wireshark sequence of the RestoreData/InsertSubscriberData Attack, with two responses to one request

As for why HiddenArt would not use the same routing system for all attacks – it does not seem to have been always reliable, especially when it comes to conversations with transactions sequences. On later dates over the subsequent years we were able to detect intermittent attack activity from Russian SCCP Global Titles themselves, related to HiddenArt attacks. We attribute this to occasional failures or limitations of the spoofing/rerouting system, this happened about 1% of the time, but for particular attacks like the RestoreData example above, Russian GTs were used ~75% of the time. This is likely due to problems like TCAP timeouts or race conditions like above when using a copying mechanism, as copying data from whatever source is slower than the SS7 connection.

Interestingly, some of the Russian GTs used in these and other attacks are in the same range as the GTs reported by the Ukrainian SBU in their analysis of SS7 attacks in their country in 2014, further strengthening the potential link. Further details of the specific GT ranges used are available to AdaptiveMobile SIGIL customers.

Stopping an Attack before it happens

At the time of these attacks, we worked with our customer to successfully detect and block them. We also shared information with the Operator Group whose source address ranges in multiple African countries were being spoofed, for them to take any action they could on their side. However the threat actor has maintained its capability since, as its periodic reconnaissance activities bear witness. We have also observed the spoofing of Mobile Operators outside of Africa by this threat actor in more recent years. Unfortunately, we were unable to determine the exact point at where we believe the data was copied from leaving the targeted network – this could be any point in the intercarrier link or in the spoofed operator. However, this is secondary to having protection in place in the targeted network. The revealing of the existence alone of this threat actor should encourage Mobile Operators around the world to confirm and improve their mobile network defences if needed, and the need for threat intelligence and analysis of attacks they receive. In addition, we hope that making this information public now, as well as the white paper, reduces the possibility of any future use of this system, or indeed any other similar system misusing mobile networks, regardless of their origin and purpose.

Many thanks to the Data Intelligence & Threat Intelligence Unit teams within AdaptiveMobile Security as well as our Mobile Operator customers & Inter-carrier partners

[1] 2020 – Percentage of attacks on US devices from Canada / Mexico – 4G: 48.50% 3G: 60.67%, Page 14 & 16 – Exigent Media Far from Home Report 2

[2] For visual evidence of information being shared within the Operator community being leaked to attackers prior to public release, see our follow-up presentation on Simjacker in VB2021. Read our Frequently Asked Questions about Simjacker as well.