The Flash – Detecting malicious super-fast SIMs on SS7 Networks

One of the interesting things when applying security to the world’s mobile phone network is that you can come across completely unexpected events that initially have you stumped, but by investigating them they can lead you to get a better understanding of the threats to the network, as well as your own knowledge. One recent event we have come across is when our systems detected a mobile phone number seemingly moving between dozens of different countries every day

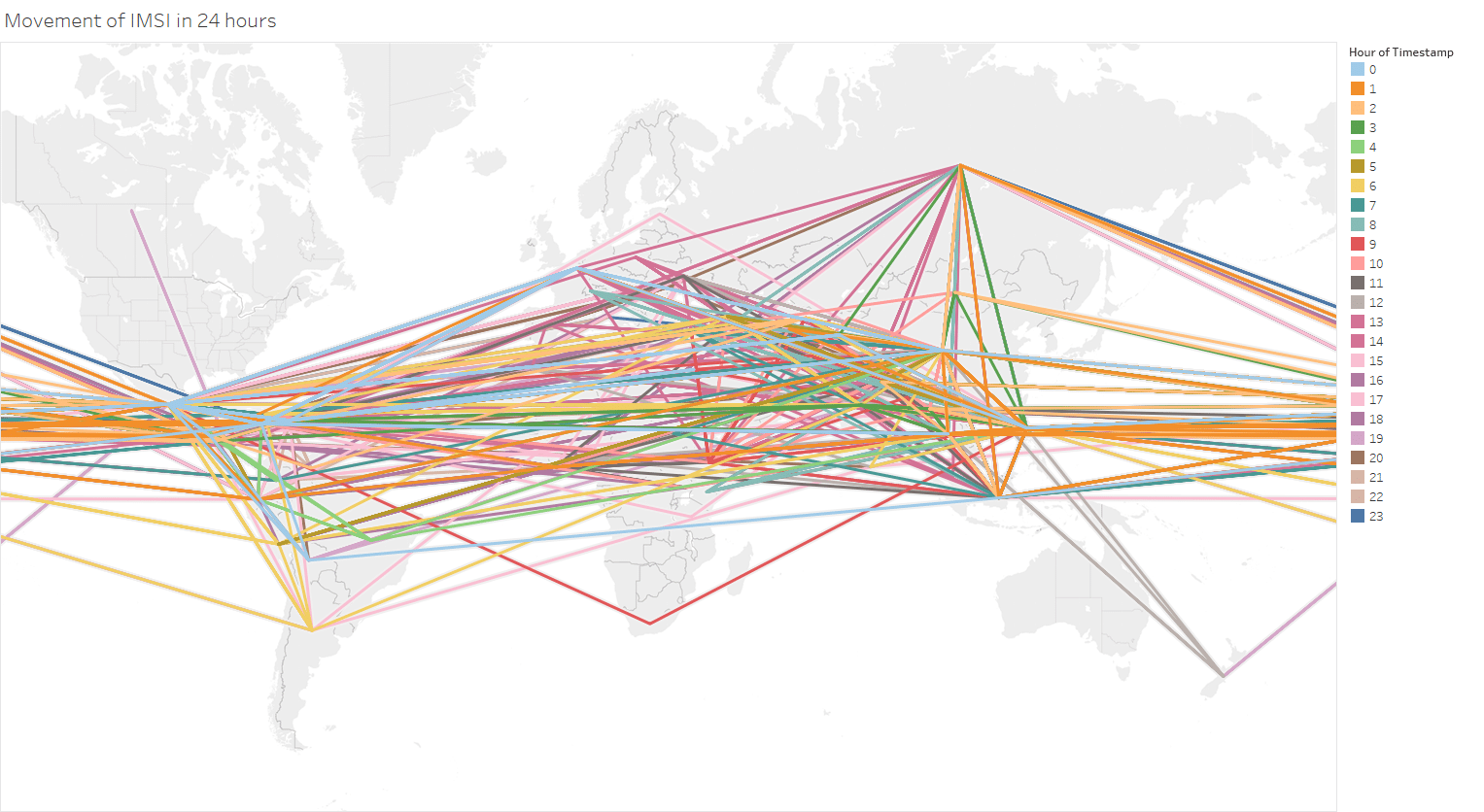

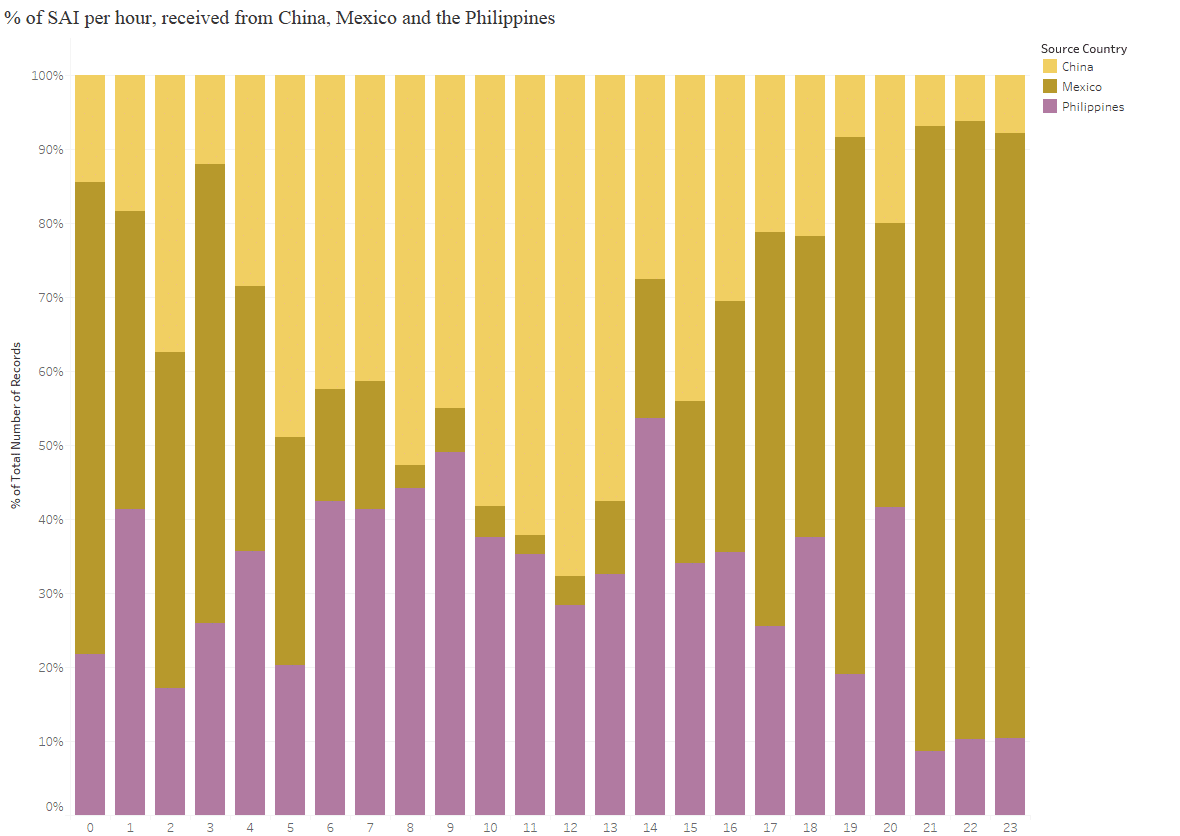

If the SS7 traffic being generated was trusted, and the mobile phone user was actually at these individual countries, then it was going at incredible, and bascially implausible, speeds. Below is an animation of a straight line path between all the different countries that the subscriber was present at each hour during the day, showing the huge range of countries visited per hour, with Mexico, China, and the Philippines being the most frequently ‘visited’.

A different way to visualize this is to show the full 24 hour activity, with the different colours representing the different activity per hour

As a thought experiment, taking the midpoint of each country, we estimated that the mobile phone achieved at one point a ‘top speed’ of 66 million km/h (41 million mph), which is 250 times faster than the Juno probe, the fastest ever human built object!. An alternative, and nerdier, way of looking at this, is that the phone was potentially travelling at 6% of the speed of light. So clearly something unusual was happening, the question is what, and whether it was a threat.

First of all, to give some context, the subscriber in question was causing SS7 packets (called SendAuthenticationInfo packets) which contained the same IMSI number (the subscriber identifier assigned to a SIM card) to be sent from multiple countries worldwide throughout the day. These packets are the first stage in a subscriber registering on a new network. From working with our customer, we soon determined the packets & IMSI were not a threat, but the question was still what was causing the behaviour. Spoofing attempts were ruled out as we were quite confident that the worldwide network elements sending the SAIs were real and they believed that the IMSI was actually in their network (you may want to read our post on detecting IMSI catchers as well).

One possible answer came when there was a mention of the IMSI on Chinese language websites also connected to iPhone unlocking and jailbreaking, (note: unlocking is the process of changing your iPhone so it can use any SIM card from around the world.) Following this clue, we investigated in more detail how exactly iPhone unlocking works.

How these unlockers work is complex and varied, but one particular type basically involves the use of a special chip, that fools the iPhone into temporarily thinking that it has a SIM card with a different ‘dummy’ IMSI in it. A YouTube video showing this is below:

You can see that once the dummy IMSI is used, the person with the phone rings a special number 112 to help complete the unlocking. And indeed, when we examined the dialling pattern of our fast-moving SIM, we could see that the majority of numbers it dialled was 112*.

So, while we could not confirm it 100%, if the fast-moving SIM was actually one of these dummy SIMs being used by an iPhone unlocker, what we were seeing is dozens of people around the world independently trying to use these chips, to unlock their iPhones. The chip would cause the phone to think it had a SIM with this IMSI for a moment, but the mobile network that their iPhone was connected to would pick up this new SIM, and then attempt to start the authentication procedure with the IMSIs home network (our customer). This would give rise to the same ‘subscriber’ to be seemingly traveling around the world, and fit the pattern we saw. The dialling of 112 that we saw also gave further evidence of this.

We could see further indirect proof of this in that activity in the different time zones seemed to be common, i.e. activity was most intense during the same hours (evening) in China and the Philippines, whereas Mexico activity was earlier, again during their evening hours.

While this case is on the minor scale of the suspicious activity we would see on signalling network – it would certainly not be on the same scale of state sponsored platforms using the SS7 network for surveillance for example – it does show the need to apply intelligence to alerts in any monitored system, be that SS7 or otherwise. Its not enough to simply have alerts, unless you apply intelligence, analysts can be overwhelmed with ‘noise’, and attacks that deserve closer attention get lost.

*Note: besides the questionable nature of the whole SIM unlock process, this use of 112 is especially problematic, it does not directly access emergency numbers in China – but it does in Europe, the US and many other countries, and so using it for non-emergency purposes is arguably illegal.